An AI-first marketing framework for 2025-2026

The AI revolution has reached marketing, but not in the way most people think.

I’ve immersed myself in AI tools for a year now, and here’s what I’ve figured out: AI can write decent code and do average marketing work. If you’re employed in marketing or software development you are likely worried that your job is being “disrupted”.

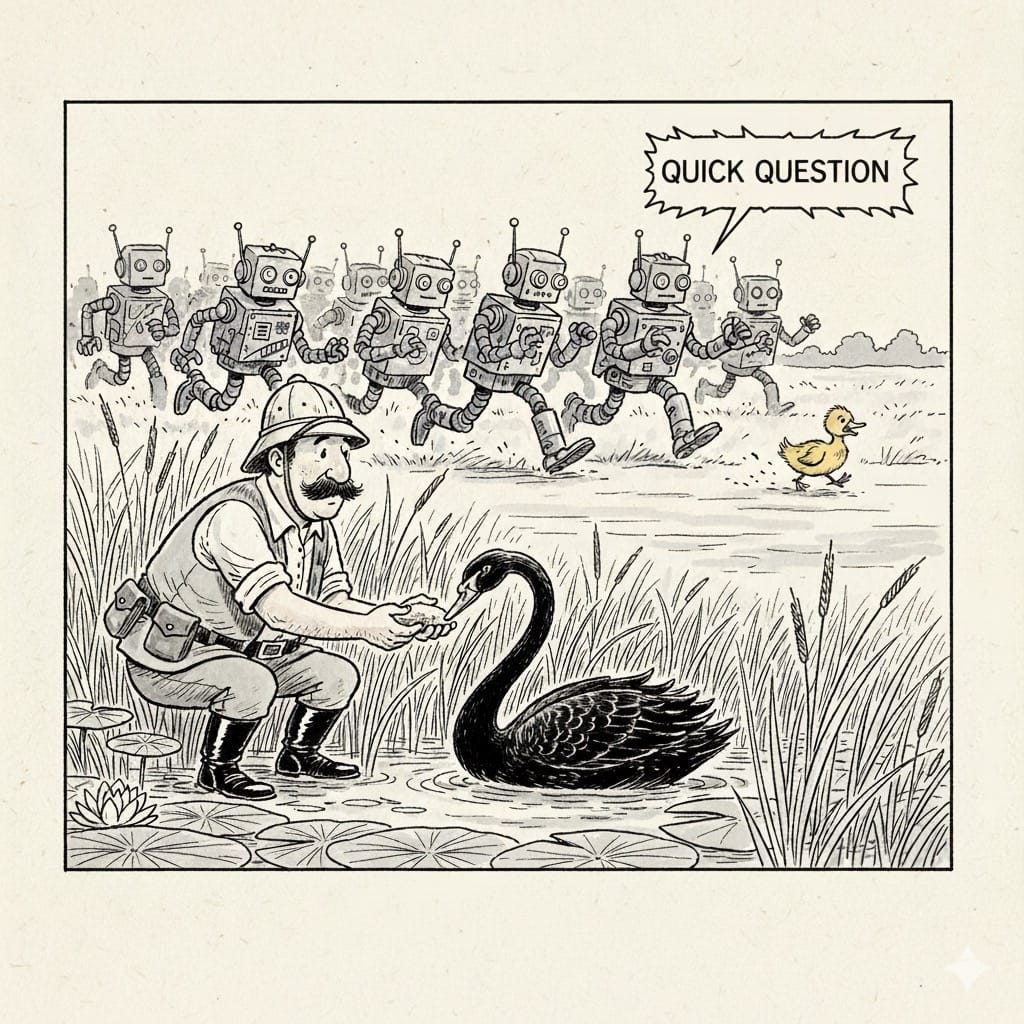

We’re now in a bubble of mediocrity: there is more supply of CRUD apps and copycat marketing than demand. Every major platform promises that “AI will do the boring parts so you can do the strategic parts” but they are light on details about what they won’t try to replace with AI.

If you've followed my work over the past few years, you'll know that I've struggled with what kind of work I want to do. The frontier of marketing and growth hacking seemed to close around 2016, as emergent social media channels gained preeminence and everyone looked to implement the same tired playbook.

Like many marketers, I found myself questioning the value of implementing this same playbook while seeing diminishing results. At first, AI seemed to accelerate this, reducing the effort to implement the same plays.

Then one day I realized: the problem is the solution. If AI commoditizes average work, there might be meaningful work left over, if we can see it.

AI is now competent at writing code, and it is quickly learning how to match parity with average marketers and salespeople. This says more about our standards than the intelligence of AI: sales and marketing have been trying to industrialize mediocrity for twenty years, and most software is just re-creating the same CRUD app.

If AI succeeds to take over the middle marketing and basic software, what remains? That’s what I’m exploring.

Business thesis

There remain 4 things in marketing that AI cannot do well: stories, segments, signals, and systems.

Stories

Stories are the sincere problems your customers faced and how you solved these problems while making them the hero. Good stories don’t look like Oracle 2-page PDFs with “Challenge” “Solution” and “Key Metrics” sections. Great stories sound like “I hired the most expensive firm because I knew they weren’t going to YES me.”

AI doesn’t uncover stories well, because most humans don’t uncover stories well.

Segments and Signals

Segments are the 500 people in the world who actually care about that story. Segments are static.

Most marketers create segments based on job title and industry. Here are three specific segments that actually converted:

- Hubspot partner in India found most their best clients had a C-Level or Board Member from India or MENA

- Cybersecurity SaaS discovered their best customers show tattoos on LinkedIn

- Bootstrapped HR SaaS sold best to leaders who started out in recruiting (lower status than HR) and had an existing tool in place that wasn’t best in class

Signals are the indicators that someone entered your segment. When I consulted for companies using Marketo, one of my favorite signals was that a company had previously worked with a specific consultant before me: I knew there would be predictable mistakes and issues in the system that I could solve.

Some signals are easier to source. Tracking when prospects change jobs is “free” if you use LinkedIn Sales Nav, with about an hour of setup. Most companies fail to even try this.

For tech marketers, today, the standard for signals is just “Buy 6Sense and run ABM.” This barely worked in 2018, and seems to no longer convert for most. The root cause is a lack of meaningful segments. To go back to the job changers: for every company that tracks job changes among their champions, there are 100 companies tracking job changers among prospects in companies they are not qualified to serve.

AI can find people that match your segments and signals, but you have to know what to look for.

Systems

Systems pull the other three together. You need systems that take the insights from stories, segments, and signals, and operationalize them at scale.

Over the past ten years, I’ve built up parts of this system organically: customer alumni in 2016, story extraction in 2020, and segments and signals since last October. Each failed on its own because customers would get stuck:

- “Thanks for finding our job changers - now what do we say to them?”

- “These quotes from our customers are gold. Now how do we use this to sell to the next prospect?”

- “That segment looks real but it is tiny. How can I grow my company with such a small niche?”

AI can help to code these systems, but AI agents cannot run this autonomously: you need deterministic software, not indeterministic LLMs.

I’ve learned you cannot solve these in isolation. You need all four pillars working together: which is why I now only work with companies ready to tackle the whole system.

My general thesis

This business thesis matters because it pokes at a deeper question: can technology extend our biological capacity for relationships, or are we doomed to cynical transactionalism and atomization?

The internet and social media accelerated a trend away from community and trust that began in the 1970s. Friends were replaced by “friends” on Facebook, shared cultural understandings were replaced by tiny echo chambers, and every person not working for FAANG has to work hard to avoid the abyss of working under the API.

I first discovered this pattern in 2012, and identified that it was affecting our lives in location, vocation, and love. In all three areas, our parents made one lifetime choice at 18, with a promise of reciprocal loyalty, and based on a handful of options.

Today, Gen Z faces an entire world of options and no meaningful way to choose.

We struggle to choose a career when new professions appear every day, and capital erodes the job security that other generations had. Today, most companies will make longer contractual commitments to their SaaS than they will to their employees.

We struggle to choose a city to live in when there are dozens of interesting unique places full of similar people, our friends are split between ten of the cities, and offer no guarantee that they will stay there for the next decade. Meanwhile the cities try to attract more people while also refusing to build the housing that enables roots.

We struggle to find love when there are 3 Billion options - and each of them have 3 Billion options of their own.

I believe the root cause is our biological limits on relationships. Dunbar has studied this extensively, and the tl;dr is “your brain has natural limits on how many people you can care about.”

Every B2B startup implicitly bets against this limit, assuming their buyers have capacity for dozens of vendor relationships. They don’t. But what if software helped buyers deepen relationships and increase capacity? Is that even possible, or are our limits hardcoded?

I’ve pondered this for 13 years now, and I don’t know the answer yet. Software before AI was built for atomization and transactionalism: every SaaS whispers “we can commoditize your humans.” Likely a lot of p(doom) comes from software developers who gaze at their work, feel the slow dystopia they helped to bring, and gasp at how much more efficient an AGI could do the same. But there is an alternative path: software can be written that centers on labor, rather than capital, that makes humans the masters instead of the servants.

Marketing serves as a great laboratory for this work. Every company that wants to grow beyond referrals has to solve the relationship capacity problem. They can usually do more to strengthen the relationships within their 150, but it takes effort and courage. AI can handle a lot of the effort, if someone brings the courage and knows what to look for.

Further Reading:

- Watch: Adam Curtis’ documentary on Hyperreality (producer of “Century of the Self”.)

- Book: Average is Over by Tyler Cowen

- p(doom) wiki

- Working under the API

- BBC summary of Dunbar’s research